Remembering the "Four Freedoms"

This Thanksgiving, take time to appreciate Norman Rockwell and the essayists at The Saturday Evening Post.

One of the most iconic illustrations of Thanksgiving was provided by Norman Rockwell forThe Saturday Evening Post. In 1943, Rockwell created four illustrations based on Franklin Roosevelt’s 1941 State of the Union Address (SOTU), also known as the “Four Freedoms” speech.

Roosevelt’s January 1941 speech laid out reasons why the United States could no longer be isolationist as a world war was raging in Europe. It’s not difficult to understand the apprehension of the American people who witnessed the horrors of the First World War and its aftermath. However, appeasement and delayed reaction as Germany built up their army and munitions directly resulted in the creation of World War II.

His speech covered domestic issues, to be sure. If you read it, Roosevelt sounds much like present Democratic Party politicians seeking to enhance social programs. Meanwhile, he stopped short of telling the American people that we would need to send troops overseas. He did, however, make the case for building up our Army and Navy at a quickened pace and helping our ally Great Britain.

How would we accomplish all of these goals? Through the raising of taxes that he sold as a sacrificial, patriotic duty. He then went on to tell Congress that if they maintained financial prudence rather than personal get rich schemes, the American people would gladly pay extra taxes.

Interestingly, eighty-two years have passed and politicians still sound the same. More programs, more taxes, with a dash of corruption. Look at what Roosevelt had on his list for domestic economics, as per the speech:

“Equality of opportunity for youth and for others.

Jobs for those who can work.

Security for those who need it.

The ending of special privilege for the few.

The preservation of civil liberties for all.”

Familiar, right?

As we know, eleven months after Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address, “a day which will live in infamy” resulted in an even more expedited need for weapons, ammunition, ships, tanks, and planes. No longer were we merely debating being on the sidelines, we were in war. World War II was not a war easily won, thus Rockwell returned to Roosevelt’s SOTU speech from two years prior for inspiration to uplift American morale through art.

According to Artnet, “Rockwell had originally wanted to paint the series for the military and, hoping for a commission, sent a charcoal sketch of the “Four Freedoms” paintings to the Office of War Information (OWI). Not only did the brass turn it down, they twisted the knife, writing, ”The last war, you illustrators did the posters. This war, we’re going to use fine arts men, real artists.” Ouch!

However, once The Saturday Evening Post ran the illustrations and the American people loved them, the government was more than happy to use Rockwell’s illustrations to support the war effort. Funny how that worked out.

In addition, each image ran in the Post with an essay to accompany them.

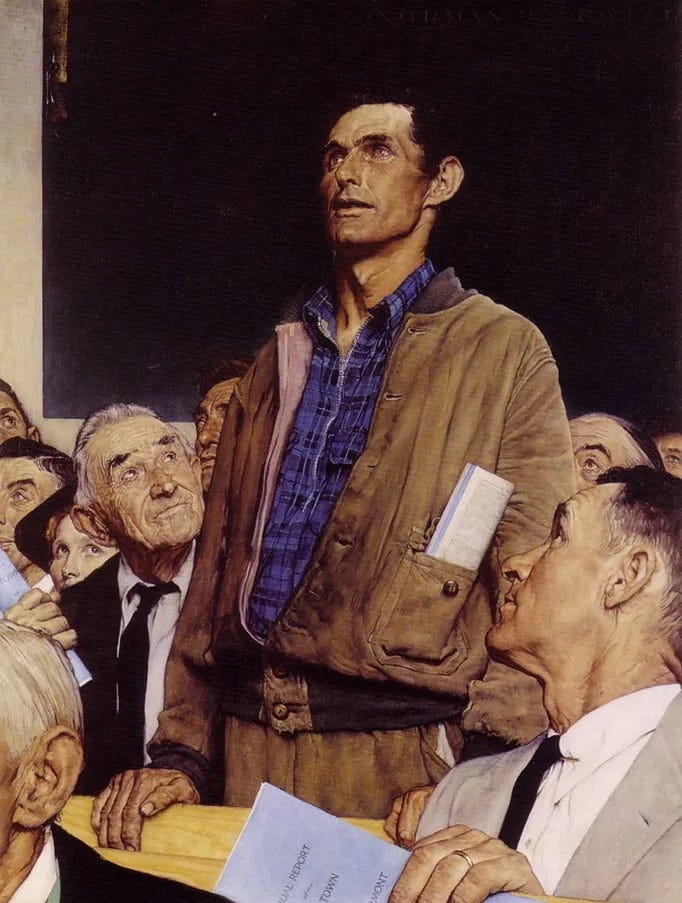

Booth Tarkington wrote a short story about “Freedom of Speech,” which is eerily prophetic in our present world. In it a journalist and a watercolor painter meet by chance at a chalet at Brenner Pass in 1912 and, after deciding they were on the same political page, discuss how to thwart freedom of speech in England and the United States.

For there, the journalist insists freedom of speech cannot be stopped. He says, “Those countries are poor fields for such as you and me, because why conspire in a wine cellar to change laws that permit themselves to be changed openly?”

Replies the painter, “Speech is the expression of thought and will. Therefore, freedom of speech means freedom of the people. If you prevent them from expressing their will in speech, you have them enchained, an absolute monarchy. Of course, nowadays he who chains the people is called a dictator.

The two continue their discussion until it becomes clear that the only way to stop freedom of speech is through a purge. But how can this be done in countries with freedom? The painter says, “…many people can be talked into anything, even if it is terrible for themselves. I shall flatter all the millions of my own people into accepting me and the purge instead of freedom.”

By the end of the story the reader comes to learn the names of the two speaking. Can you guess?

How extremely eye opening this short story was at the time, for sure, but parallels our current American society. For example, New York Governor Hochul just announced she is using $3 million to combat hate speech and provide her Media Literacy Toolkit for K-12 students to understand how to spot disinformation. Trust her. She’s in the government and has everyone’s best interest at heart.

Now, look carefully at the illustration by Rockwell. You will see that the man speaking is common, perhaps a farmer judging by his farmer’s tan and rough hands. He confidently stands and speaks amongst those more well dressed at a town hall meeting discussing finances. Most importantly, he is being listened to without interruption. He is fearless and knows his voice is equal to everyone else’s. This is the meaning of freedom of speech, as opposed to what we are witnessing at today’s school board meetings.

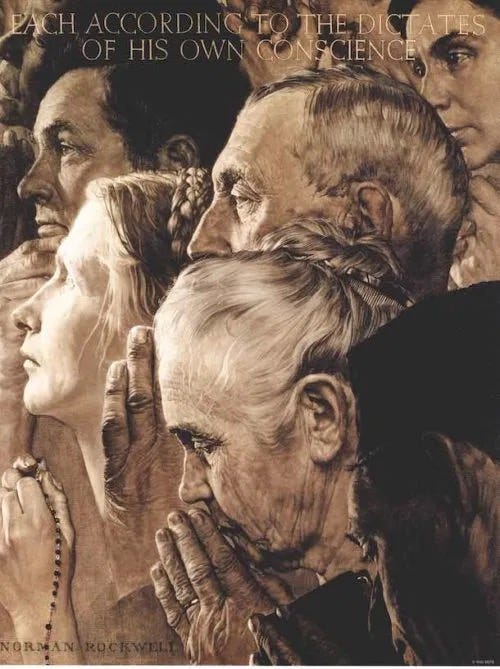

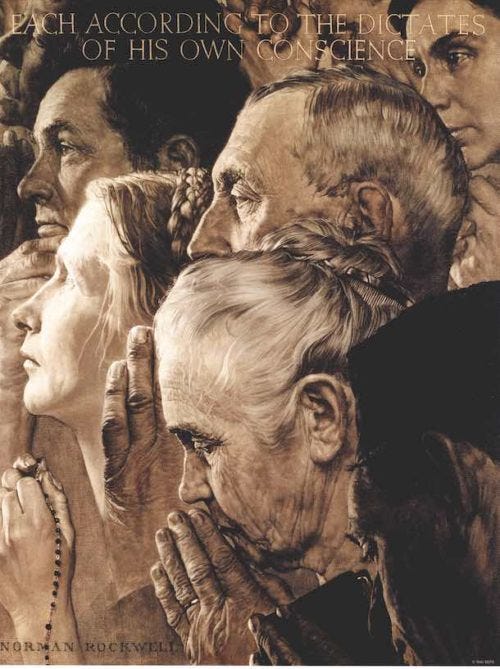

The essay accompanying “Freedom of Worship” was written by Will Durant. In it he describes the men and women of faith on which our country’s founding was based. He writes that man and beast are separated by man’s ability to laugh and worship, that our country boasts many faiths including the faithless, and that freedom of religion is under assault by dictators who persecute those with faith because they, themselves, wish to be powerful gods. Will wrote, “No ruler has yet existed who was wise enough to instruct a saint; and a good man who is not great is a hundred times more precious than a great man who is not good.” This essay is truly a gem to be read and savored. Once again, we are facing religious persecution today.

What makes this essay so special is that the author claims to know nothing except what he reads in books. To him, faith is intangible and personal. What is it that makes families who toil all week, show up to church dressed “in the uncomfortable finery of a Sabbath morn?”

Of all the freedoms, Durant finds religion the most important. He adds:

“It is incredible that such reactionary madness can express the mind and heart of an adult nation. A man’s dealings with his God should be a sacred thing, inviolable by any potentate… When we yield our sons to war, it is in the trust that their sacrifice will bring to us and our allies no inch of alien soil, no selfish monopoly of the world’s resources or trade, but only the privilege of winning for all peoples the most precious gifts in the orbit of life — freedom of body and soul, of movement and enterprise, of thought and utterance, of faith and worship, of hope and charity, of a humane fellowship with all men.”

And Durant was correct. Our men did not fight WWII as a land grab. Instead, we fought for freedom. You cannot chain a man’s soul. It will not surrender to outside forces. Instead, the human soul will be forged like steel under the pressure of those who want to strip them of faith. God and how we worship—or not— has to do with our life’s journey. It is truly an inalienable right.

Rockwell’s illustration is powerful for no one religion is considered more important than the other. His use of a more sepia color palette helps provide the sense of an equality of religions. No government agency dictates how we pray.

But times have changed. The tired argument of a division between church and state is prevalent, yet social justice is seeping into our religions. St. Mary’s College of Notre Dame is an all-women’s Catholic college that is now accepting those who identify as women. At the same time, they rejected a student’s request for a chapter of Charlie Kirk’s Turning Point USA for conservatives on campus. Something is gravely amiss.

“Freedom from Fear” written by Stephen Vincent Benét focuses on the fears that mankind has had since the beginning of time. Be it a fear of nature or fellow human beings, mankind has hungered to learn why bad things happen. Through education by “wise men and teachers” fear was reduced. Disease, pestilence, and ignorance of the past was now eradicated, so our children and their children would not have to live in fear. He then writes how those seeking freedom come to America:

“So, in our corner of the world, and for most of our people, we got rid of certain fears. We got rid of them, we got used to being rid of them. It took struggle and fighting and a lot of working things out. But 130 million people lived at peace with one another and ran their own government. And because they were free from fear, they were able to live better, by and large and on the whole, than 130 million people had lived before. Because fear may drive a burdened man for a mile, but it is only freedom that makes his load light for the long carry.”

But Benét adds that due to the creation of the airplane, the world got smaller. Our little “corner of the world” could not drive out the opposing forces of danger that comes with new technology. Benét hammers home the point that bombs can drop on us at any time now that oceans can be traversed with flight. He continues, “But innocence, good will, distance, peaceable intent, will not keep those children safe from the fear in the sky.” Instead, it will take the world coming together to keep fear at bay. We cannot shrink from responsibility for, “We do not intend to breed a race wrapped in cotton wool, too delicate to stand rough weather. In any world of man that we can imagine, fear and the conquest of fear must play a part.”

After eighty years can we still say this? Or have we bred a race swaddled in bubble wrap. Everyone in America is so separated from each other purposely by class, race, sex, gender identity, culture, sexual preference, etc. Art is offensive, books are offensive, religions are offensive, statements are offensive, words are offensive. Safe spaces abound, and all of this fear mongering is crippling individuals and our collective idea of what it is to be American.

Rockwell contrasts the innocence of the children asleep between crisp white sheets, being tucked in by their mother with the father who is clutching his glasses and newspaper with a headline of war. Toys are haphazardly on the floor but the newspaper is still folded waiting to be read. The parents fear for their children’s future but are protecting their innocence as long as they can.

Children tug at our heartstrings, which is why current images emerging from the Middle East are disturbing. Children are no longer kept protected, they are being used in war propaganda.

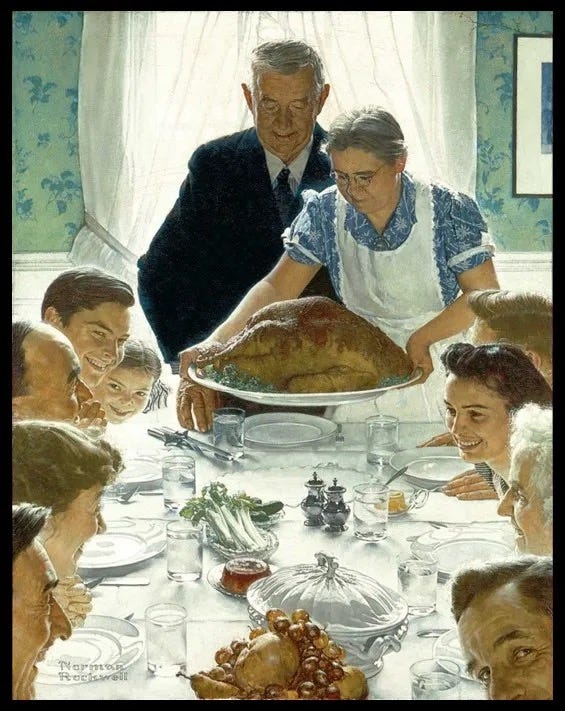

Lastly, is “Freedom from Want.” Interestingly, the most recognized of the four Rockwell paintings is jarringly merged with a piece written by Filipino American Carlos Bulosan. The painting of a white family sitting around the table immersed in their own conversations while grandma is laying down the roasted turkey contrasts with Bulosan’s more pro-union, progressive views. He speaks from a place of an unwanted immigrant, left to menial work.

His closing argument for the freedom from want sounds like a Bernie Sanders speech:

“We are the sufferers who suffer for natural love of man for another man, who commemorate the humanities of every man. We are the creators of abundance.

We are the desires of anonymous men. We are the subways of suffering, the well of dignities. We are the living testament of a flowering race.

But our march to freedom is not complete unless want is annihilated. The America we hope to see is not merely a physical but also a spiritual and an intellectual world. We are the mirror of what America is. If America wants us to be living and free, then we must be living and free. If we fail, then America fails.

What do we want? We want complete security and peace. We want to share the promises and fruits of American life. We want to be free from fear and hunger.”

But as liberal as Bulosan’s writing appears, it was more in keeping with the world at large at the time. Americans may have enjoyed Rockwell’s painting but in war-torn Europe, it wasn’t met with acclaim. The scene appeared to show over-abundance. But we are America, the land that eventually produced the popular show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. Is there such a thing in America as too abundant? That’s the question being raised today across college campuses as they try to earn a living on Instagram.

And so during this Thanksgiving week, the call to remember the freedoms we have but have taken for granted are resounding. No other country has had the freedom of speech, the freedom of religion, the freedom from fear, or the freedom from want as much as the United States of America. Our ancestors traveled in a small cargo ship called the Mayflower in order to escape religious tyranny and created their own political system based on the will of the people (i.e. The Mayflower Compact).

We have not had an easy road. But especially since WWII, we should have learned how tenuous our threads to freedom can be. Do we awaken from our complacency and get rerouted only when there is a world war? It certainly feels that way.

I urge you to read each essay for yourself at The Saturday Evening Post archives, look closely at these illustrations, and understand that we have so much to be thankful for because we are truly blessed.

Beautiful!